With the container terminal spared by the double explosion which damaged part of the port infrastructures, professionals in the sector hope to resume their activities, at the very least, within a week.

This article was originally published in French.

It is not an understatement to say that the Port of Beirut is vital for Lebanon. On its own, it received 73% of the goods imported in 2019 in value, or $14 billion out of a total of $19 billion (at a rate of 1,500 pounds per dollar), and collected the bulk of customs duties on behalf of the government, which totaled $1.2 billion in the same year. This is not to mention the $199 million in port revenues generated.

This nerve center brings together a multitude of players and employs more than 5,000 people, according to Amer el-Kaissi, president of the Lebanese forwarders syndicate and CEO of General Transportation Services (GTS).

Employees are distributed among the entity that manages the Port of Beirut (GEPB – Beirut Port Management and Operations), the company that manages the container terminal (BCTC – Beirut Container Terminal Consortium), the Army, Public Security, customs, the pilot station, shipping agents, freight forwarders, transport and logistics companies, handlers, ship chandlers and waste collection companies, not to mention more than a thousand truckers.

How many of them were at the scene on August 4 just after 6 pm when a terrible explosion devastated a large part of the port? How many lost their lives? How many were injured? It is still too early to say, as the search under the rubble continues.

The lucky ones, however, had already left their workplace. "Fortunately, if I dare say, the explosion took place after the offices were closed, otherwise I could have lost 50 employees," said Mourad Aoun, CEO of the logistics company Net Holding, whose two warehouses and offices in the port's logistics zone went up in smoke. "The material damage is important, but it isn't the main point. The important thing is that our employees are safe and sound and that they can go back to work," he added.

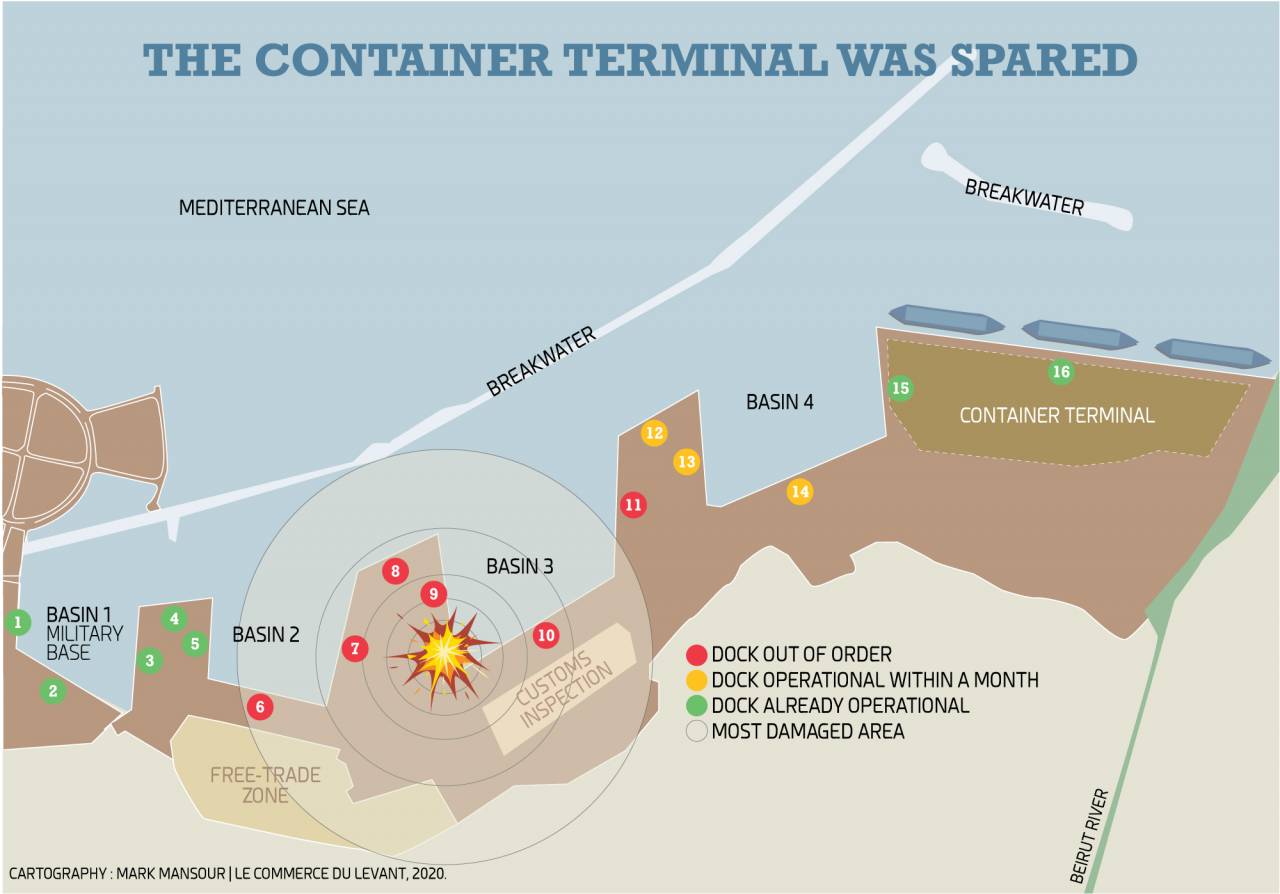

The explosion, which took place in basin No. 3, damaged all the premises in the area, including the customs building, as well as the warehouses in the port's free zone, where goods were stored. The docks in this basin as well as part of those in basins No. 2 and No. 4 are now out of use (see map). These docks were used to import bulk goods such as wheat, seeds, livestock, cars, metals, etc. The port's pilot station, located on dock 6, was heavily damaged and lost nine of its 10 pilot boats and three of its five tugboats.

The Container Terminal Operational

But other parts of the port seem to have been relatively spared, notably the container terminal where the bulk of port activity is concentrated. "Most of the cranes installed in the northern part of basin No. 4, at the end of the port, were damaged. Docks 15 and 16, which alone provide about 60% of the activity, are still operational," explained the general manager of the port's pilot station, Mohammad Ali Baltaji. The container ships Vessel Electra and Nicolas Delmas, the latter belonging to CMA CGM, were thus able to enter the Port of Beirut on the evening of August 10.

In basins No. 1 and 2, operated by the Lebanese Army and the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), were also put back into service. As for docks No. 12 to 14 in basin No. 4, "they should be rehabilitated within a month, which would allow the port to regain 80% of its pre-August 4 level of activity," Baltaji said. "The fuel and gas tanks along the coast in Dora haven't been damaged either, which should allow the ships to get there," he added.

Most companies in the sector are therefore preparing to restart their activities in the coming days, at the very least, bearing in mind that the Port of Beirut was already operating at a slower pace before the disaster because of the economic crisis, which resulted in a drop in imports, at an annual rate, of more than 50% over the first five months of the year. “We were ready to redirect all our activity to the Port of Tripoli, but we have since suspended this decision and are now able to operate, in part, from the capital's port," said Viviane Mnayerji, commercial director at Henry Heald & Co – a shipping, forwarding and stevedoring agency.

To speed up the recovery, el-Kaissi said he had asked customs "to move all goods through the green line (a line on which goods aren't subject to customs controls), knowing that the inspection facilities on the red line have been destroyed." He estimated that "1,500 to 2,000 workers could be back to work at the Port of Beirut within a week."

The alternative of the port of Tripoli

This is a relief for the employees, as some of them have no real alternatives. If large companies, which already have the necessary licenses and offices in northern Lebanon, expressed readiness to relocate to the Port of Tripoli, such as the CMA CGM group, a shareholder in the Gulftainer company (which manages the container terminal there), others would have found themselves in a bad situation.

Apart from the capacity of the Port of Tripoli to absorb the entire flow of goods destined for Beirut – knowing that in 2019 its share in the country's total imports did not exceed 5% – such a scenario would have posed the risk of social and sectarian tensions. For even port activity, unfortunately, is subject to confessional criteria.

"As a Sunni, I might have been able to find my place in Tripoli, but that would certainly not have been the case for everyone," said a freight forwarder at the Port of Beirut, requesting anonymity. "The demographic and political distribution is different there and, therefore, so are the working arrangements," he added. This prompted the president of the Union of Truck Owners at the Port of Beirut, Naim Sawaya, to say that out of the 1,000 truckers working at the capital's port, "only 150 to 200 could have worked in Tripoli."